AND PARFITT: Master & Commander

AND PARFITT: Master & CommanderAndy Parfitt, owner of the hefty title ‘Controller of Radio 1, 1Xtra, Popular Music and Asian Network’, arrives on stage. His time with us is opened with a retrospective account of how the seed of his radio-acorn was first planted: "In Bristol, where I was growing up, my mother was always ‘worried about me’. My interests were my bicycle and the band that I was in, and that was about it. I loved doing the sound for my band and I loved the radio, right from early doors. My dad bought me a radio for Christmas and I discovered Radio Luxembourg, Radio 1 and Radio 4 and was a radio nut. My mum spotted that the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School had been criticised in the Bristol Evening Post for never giving a space at its prestigious production course from anyone in Bristol, so she wrote off to them –‘You should see my son’. They called me for an interview, and on my walk up, it hammered with rain and I turned up to the posh Bristol Old Vic Theatre School and was interviewed looking like a drowned teenage rat… and they gave me a place. So that was my little bit of serendipity."

But it wasn’t just a simple penchant for the airwaves that got him to the heady heights of radio overseer. Andy soon makes us aware that from an early age he had a determination that would see him though to maintaining his current position for well over a decade (he was made Controller in 1998): “When I was on the course, I took every opportunity to meet people who do sound; I pursued it. My ambition was to be John Peel’s sound engineer. That was it. I did achieve it in my 20s; I did the John Peel Sessions and was his sound engineer. I never had a career plan as such; I just followed my enthusiasm and my passions so that by the time I set my sights on the big things, I therefore got to do it. I wanted to become a programme maker, so I worked for BBC Education, the original Radio 5 and I got to make features for Radio 4, the pinnacle of what British and world radio is; an institution."

Talkin’ Bout a Revolution

Andy has a presence on stage that exudes confidence. A natural public speaker, like a teacher captivating the obedience of a classroom, he talks with passion about the BBC: “I did my time a funny way round, but I went to the BBC 1 because I wanted to learn, I was curious, I was passionate about its purpose as an organisation. I am a real BBC believer, I believe in the public service ethos of the BBC. I thought that it needed to do a job for music and young people and that was my drive to get there. Media has changed so utterly completed since 1967 (the Marine Broadcasting Offences Act was brought in citing pirate radio stations to be illegal); it should be a happy companion to your young life. The media landscape and technology has changed, with a purpose of supporting new music, producers, talent, artists, genres and music scenes. What the BBC calls its ‘democratic purpose’, young people aren’t buying The Times or watching Newsnight. The under 25s consume news in a different way. Our news service is one of the key, if not the only channel of proper, impartial, accurate news for international affairs, so it has a couple of really important purposes. And the environment for most media for young people is a huge lake of commercial media, so it is the only public funded voice to go with that, which I think is very important. So that is what my passion is about, what my purpose is.”

Busy doing nothing

On his day-to-day, Andy initially starts off with what initially seems flippancy, soon backed by a shoulder of responsibility that Atlas would empathise with: “I try to do nothing; in the sense that I don’t do programme production. I try to think about the future, what needs to be done for the longer term because people are very busy working of the short term; this week, this month, even this year. But my job is to think about what is the story for Radio 1 for young people, what’s happening in that market, how is it transforming into that digital web based world. It’s a strategic job. I do a lot of coaching work with my team; I give them responsibility. Then I represent Radio 1 and spend a lot of my time around the BBC making sure they know what I’m doing, or I’m out at Westminster, or in educational establishments, universities, talking, talking, talking like this, about the public value of what BBC Radio 1 represents to young people in the country. So I spend a lot of my time being accountable. I suppose I look after the money as well, deciding what we spend where, and I try to lead creatively. I also fire fight if things go wrong (he mentions the Blue Peter cat-naming competition and Brand/ Ross scandals as his hardest career moments) and handle it with the press team, and then of course I have Radio 1, 1Extra, BBC Asian Network and BBC popular music, which I have to do all of those things for.”

So with the suit comes a cavalcade of corporate boxes to tick, not to mention the people-management skills required to handle the minds and mouths of over 30 DJs: “My job is to encourage their creativity, their personalities, their innovation, but I get them to understand the vision of Radio. DJs are very entrepreneurial individuals; they’ve worked very hard to get where they are, and then I come along and say ‘no, you are part of a team’. Good proper adult goings-on in the workplace is important to me, for morale and performance. It is my job to ultimately take responsibility for everything they say or everything they do. It’s like a family with kids; you’ve got to make sure that the repercussion for certain behaviour is appropriate. Good old BBC word there, ‘appropriate’."

Continuing this paternal outlook, with both grace and corporate cool, Andy astutely defends the subject matter of both his and Chris Moyles’ salaries: “Like in many other arenas, like in sport, you have to compete for the very top people; you have to compete in arena of the money that’s in the commercial world. Chris (Moyles) can hit any junction, to any split second, on any radio station. That guy has been on air for 52 hours straight and he didn’t make one technical mistake (when he did his Comic Relief marathon) because he’s an extraordinary broadcasting machine. The money we pay for our DJs is way below what they might get paid in the private sector for a commercial broadcaster and that discount is because the BBC is a brilliant place to work, it has brilliant opportunities it gives brilliant training, in Chris's case it gives the opportunity to build a creative show. For many people, this may feel out of kilter, and what the BBC has said about senior pay (BBC senior manager positions are being reduced along with their salaries), top talent pay also is managed really carefully.” I can’t help thinking to myself that he’s been asked this before.

Video killed the radio star?

When the time moves onto the future of radio, and the subject of whether or not it is a dying art, presenter Lisa is warned that this is his favourite subject matter and she’ll be hard pushed to stop him talking: “If you look at older people in the UK, they are listening to more radio for longer. They love it; radio is in a golden age, unquestionably. Radio does wonderful personal, companionship things that other media doesn’t. Radio for young people isn’t a dead duck, but the amount of time people spend with a pure radio opposed to what they might download or view online has changed. The broadcast reach of a programme; say Adele’s performance on Fearne Cotton’s Live Lounge on that day may be 2.5 million. But then it will be downloaded by a further 3-4 million requests to watch the video. It’s about making that transition."

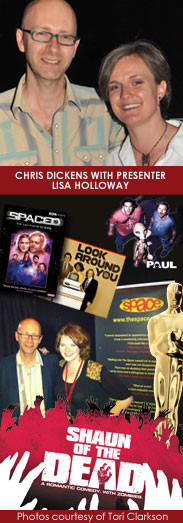

CHRIS DICKENS: Cut above the rest

CHRIS DICKENS: Cut above the restIn stark contrast to the composed and perhaps rehearsed demeanour of Andy, our headline guest of the night is evidently not so used to the limelight. Humble and maybe a little nervous, it takes Chris Dickens a measure of time to settle in. You may not be familiar with his name, but Chris’s work precedes him, having been responsible for editing TV series ‘Spaced’ and ‘Look Around You’, plus a filmography including zombie romance ‘Shaun of the Dead’, alien adventure comedy ‘Paul’ and coming of age kooky romance ‘Submarine’.

After struggling to find the right words, Chris tells us of the time surrounding his Oscar win for Best Achievement in Editing (2008) for ‘Slumdog Millionaire’: “It was amazing, unique really. It was a chance to shine. It is obviously my most known and successful film that I have won awards on (he has won a further 6 awards for Slumdog), but at the time you would never have imagined, as it was a small film, on a small budget, with stars who were not really known. A voyage into the unknown. I just wanted to go to India and experience it. You never quite know how something is going to turn out.”

Accidents in the workplace

One of the biggest surprises of the night for me came with Chris telling us how he inadvertently got the job in the first place: “I got involved more accidentally; somebody else couldn’t do it. It’s very sad in a way as editor Chris Gill, who has edited four of five films with Danny (Boyle), couldn’t do it - these things happen. So I went to meet Danny and the first thing he said to me was ‘Why is Hot Fuzz so long’? Which I thought was a really good question; he put me right on the spot! And I basically blamed the director, which Danny didn’t mind.” With the audience still laughing from his honest admittance, Chris continued: “I’d read the script and had a good feeling about it, I thought ‘this is something special, an adventure’, and speaking to Danny, this is an actual quote, his philosophy is ‘if you’re not taking risks, there’s no point turning up’; that’s what he said to me. And I understood, that’s how you try something. On paper that film was beautifully written. It was an interesting book that it was based on but very ambitious; children who were 6/7 years old and this whole idea of moving through 3 stages of their lives; we have them as adults, as older children and young children and it looks great on the page, but how is that going to work? And also half of it’s in Hindi and part English; I was worried ‘are people going to believe they start talking English?’ So that’s what interested me; the adventure, the ambition of the film.”

So, from a shy talker, we discover a chap, slowly emerging, who can weigh up the pros and cons and make a decision based on the life experience and personal development he will get from it: “The initial risk was just going out to India, only a few of us went out so we had to work a lot of locals which was a great experience in the end but very difficult; going out to an alien world, trying to make a film. Working in your country at the best of times can be difficult, but India was very difficult culturally. We would ask ‘can you do this now’ but ‘now’ meant ‘perhaps tomorrow’ over there. Well, actually I was too soft. I would say ‘maybe tomorrow it’ll be alright, you can do this for tomorrow morning’, and it wouldn’t happen. Then the next day you’d say ‘maybe later in the day is fine’, and then it doesn’t happen. And then I realised what you had to do was to jump up and down and to shout ‘I want it now!’ and it did happen. We needed some curtains in the room for instance, and within the hour five people had come in with tailor made curtains. So we got to understand culturally what the place was like, which was important for me because having that experience in the end really helped me edit the film.”

Speaking highly of Slumdog director Danny Boyle, it seems the pairing of personalities may be the key to the successful piece of cinema: “Creatively I never felt it was risky because I felt that Danny is particularly very interested in experimenting, he allows that to happen allow the cameraman to experiment, particularly me, he was not scared of failing. To me that what making a film is about; you develop it through the editing, you tell the story in a different way; you make something that works on the screen, rather on the page.”

Anything goes

Aspiring editors in the room were next given the treat of what preparation techniques were employed and just how the film won it’s trophy in time travel traversing: “Danny asked me to watch a lot of Indian films; they are great because anything goes. You can have a song and dance and then get on with the rest of the story, which in a way is bad, but then also good as it frees you up, you can try all sorts of things. That why I like Nic Roeg’s films; he plays with time a lot; a lot of flash backs, flash forwards, which is really essential in Slumdog. What I really took from watching some of his early films, particularly ‘Don’t Look Now’, ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’ and even ‘Walkabout’, it’s almost like you are watching memories, which happens a lot in Slumdog; it has a lot to do with how you recall things. Memories aren’t structured, they come through in waves, in a more random way, and that I thought was quite inspiring. It meant that we could put flashbacks in places you might not expect.”

Among Chris’s editing credits thus far, it seems his CV spans from quirky cult to fabulous feel-good. But he explains how the editing of different genres can change the tone of the whole piece: “It’s a cliché but you shouldn’t really notice the editing in a film; but as an editor I do notice. Essentially the aim is to make a film that people enjoy and like the movie as a whole, rather than think ‘that was great camerawork’, or ‘that was a great cut there’. It’s not about you, it’s not my film; it’s the director’s film, the producer’s film, and that’s what you have to remember. You’re working with these people; you are trying to get what they've written and shot onto the screen, and interpreted it the way they wanted. So you could say the editor is the unsung hero, but that’s the way it should be. Every cut you make has to have a reason, and that reason comes from ‘what story are we trying to tell?’ or what feeling you want, or how you want the characters to come across. Going further, a comedy might be about timing, and you need a cut in a certain place to make people laugh. Editing’s quite crucial for comedy. I think it’s very hard to make something that isn’t inherently funny, be it on the page or how it is performed, funny later. And people often make that mistake. Simon (Pegg) and Nick (Frost) for example are just very funny to look at and their behaviour is funny, so you are working with good material, but you can certainly wreck their performances if you’re not careful. But we don’t work in a bubble either; the directors always watch it and we test the films on audiences. With comedy you can really quantify whether it’s working or not in terms of the comedy. It’s a little harder to work out if it’s working on the whole, but you still get a feeling. That’s why comedy is rewarding.”

Looking to the future

“I’m currently working on a very strange film about filmmaking. A very low budget film, it hasn’t got a definite title but I think it’s going to be called ‘The Equestrian Vortex’ and the director (Peter Strickland) has only done one film before called ‘Katalin Varga’. It’s to be shot in Romania about a sound editor who goes to Italy to make one of those horror films like Hysteria in the late 70s, and they are doing the soundtrack. He’s an Englishman and they are all speaking Italian, and you never see the film, you just see them making the sound effects or doing the voices to the film. It’s like a David Lynch nightmare film and a Roman Polanski suspense film; it’s like you are pulled into the soundtrack of this film they are making. It sounds very obscure but it’s actually very interesting. It won’t be Oscar winning I wouldn’t think, there are no big stars or anything. It’s interesting for me partly because it experimenting again as you can’t do that all the time, but it goes back to not being afraid to try.”

It’s safe to say that Slum dog Millionaire was a cinematic success. But with speculation of a possible ‘Slumdog Millionaire 2’, it seems Chris would welcome the sequel with open arms: “The film was partly based on another book called Maximum City, which is great actually. It was written by a journalist who left Mumbai, and then went back to rediscover it. It’s about all the people who live in the city, all the walks of life. That book I’ve heard, they potentially want to make. I think Chris (producer Christian Colston) has optioned it, and it’s sort of a documentary as well. I think it will be a very difficult film to make but if they do it, I’d love to be involved, it’d be very interesting.”

Conversation moved on to Chris’s prized possession; his Oscar. But where to put it? On a shelf in the WC? On the mantelpiece for all to see? Where exactly does one home an Oscar? “Funny you should ask! The Oscar is actually hidden away because we had a house burglary. They didn’t steal the Oscar, which is amazing, but they did try to see if it was gold and realised it wasn’t, and so left it. So I thought I’d better hide it.”

Throughout his time with us at the event, Chris continuously spoke in high regard of all the cast and crew he has worked with, which I suspect is reciprocated as he comes across as truly being suited to his career choice. Even of the slightly more challenging moments encountered, he mused with a great smile of affection: “In Slumdog I could have continued editing that film forever because I just loved the faces in it, particularly the kids. Normally you do build up a relationship because you are really delving into their performance, but in reality it is really difficult to have actors in the editing room, because they are seeing different things on the screen they don’t like. Simon and Nick came in a lot during Paul because they wrote that, and they were in it, so that was slightly tricky because they were part of the process, saying ‘Oh don’t like that’,’ well why don’t you like that? ‘Well because I don’t like that shot of me’ or ‘I wish you hadn’t used that shot’. But it’s hard because you can’t really make decisions based on that. But they are great to work with. I loved working on Spaced too. Edgar (Wright) liked shooting lots and lots of stuff, he has an idea of how he wants it to all fit together, but he also has a B, C and a D plan. He shoots to edit in a way. But it was sometimes very hard; it was one of the first things like that I had ever done. I’d never worked with Edgar before, he was a lot younger than me, and actually taught me a lot of things. He’s a very good editor as well. The problem is that I’d leave the room to go to the toilet and he’d have jumped on the editing machine and we literally had to fight each other; he’s so keen to get on with it.”

To conclude the night, we ended on another inspirational, formative high as Chris encouraged us all to always see the possibilities in the smallest venture: “Do it, get to the practical part as soon as possible. The theory is never going to get you anywhere, you need to get filmmaking. Getting an actual job, you need to know a lot of people. Build up an itinerary of friends and relationships working in whatever industry it is you work in and do any job. I started in documentary films as an assistant making the tea, and then I was interested in sound, so I did some sound editing and recording. Lots of jobs for no money, then lots of shorts films. Not only do you build up practice so when you do get a chance to do something bigger; you can do it, but you also get to know all these brilliant people. Spaced again was an accidental thing - the editor dropped out and they called me, and that ended up with me doing a film with them three years later. Don't burn any bridges.”

No comments:

Post a Comment